12 December

Should we be concerned about the sustainability of public debt in the Eurozone?

Faced with a succession of shocks (pandemics and soaring energy prices), governments have allowed their deficits to grow in order to limit the economic and social consequences of the shocks. The "whatever it costs" approach to maintain incomes during the pandemic has been followed by the "whatever it costs" approach to protect purchasing power despite surging energy prices. While low unemployment figures illustrate the success of these policies, the rise in public debt provides an idea of their cost: between 2019 and 2023, public debt rose by 6 points of GDP in Germany, 8 in Belgium, 9 in Spain and Italy... and more than 12 in France! Even so, this rise in debt does not fully reflect the accumulation of deficits.

The cost of "whatever it takes" lightened by inflation

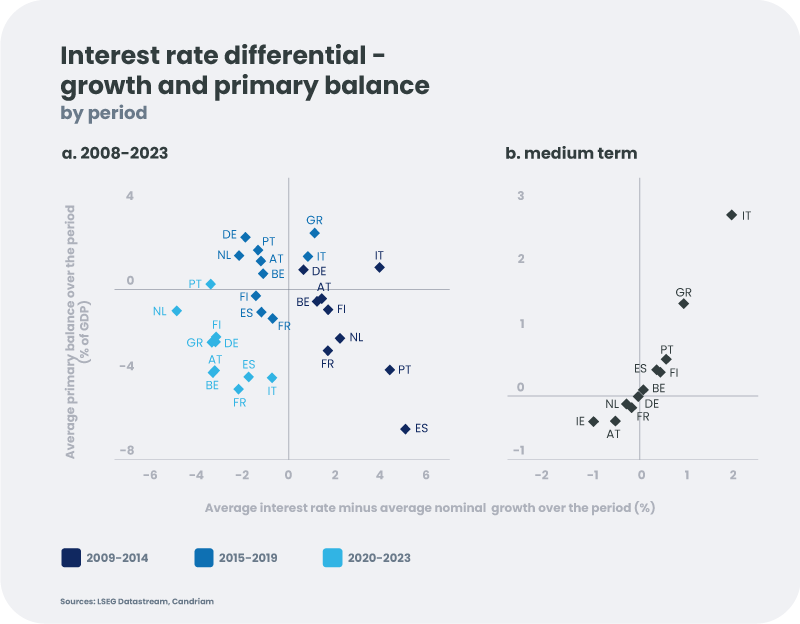

Equation (2) in the box shows that the debt burden increases not only with the primary deficit (i.e. the deficit excluding interest charges), but also with the difference between the average interest rate on the debt (i) and nominal growth (g). This effect, usually referred to as the "snowball effect" - it increases the debt burden when the i-g spread is positive - had this time attenuated the increase in the debt burden (the i-g spread being negative). Between 2020 and today, governments benefited from a favourable window of opportunity, during which nominal growth above the average interest rate has helped to lighten the "whatever it takes" bill (graph a). It should come as no surprise that this effect came into play at a time when the interest rates at which governments were increasing their debt burden were rising sharply. With an average maturity of around eight years, only a fraction of the debt is renewed at market interest rates: any rise in these rates is therefore only very gradually passed on to the average cost of debt. The effect of soaring prices (and therefore nominal growth) on the debt burden, on the other hand, is instantaneous! But the window of opportunity is now closing...

A less favourable arithmetic

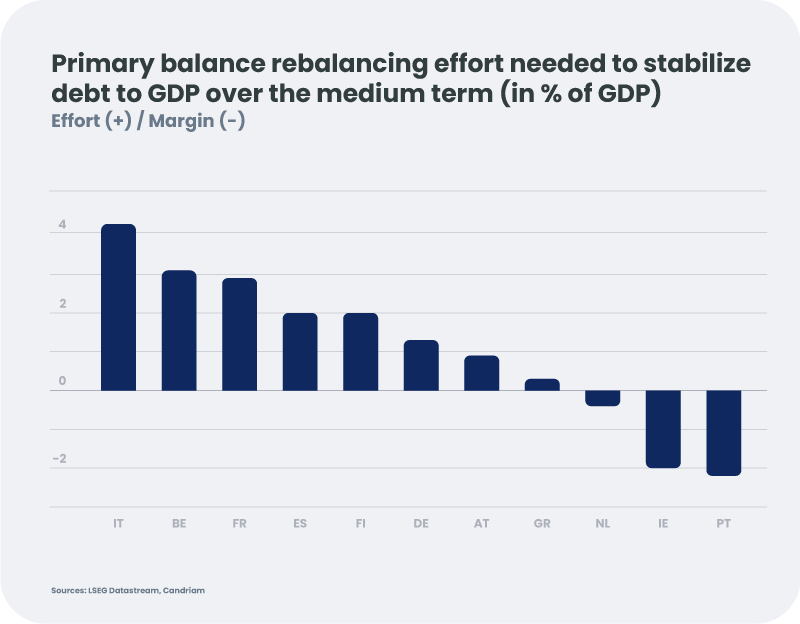

With the debt burden rising and primary deficits still high compared to 2019, governments are entering the next few years in a less favourable position. While the average cost of debt will continue to rise, falling inflation and weak growth prospects won't help. In the medium term, European governments have no choice: if they are to avoid a drift in their debt burdens, they must bring their primary budget balances back into balance (graph b). The equation is even more complicated for Italy: with a high debt burden, high interest rates and relatively weak growth, it will have to generate primary surpluses on a long-term basis.

In the end, for at least three countries, the efforts required over the next few years are far from negligible: France, Belgium and Italy must reduce their primary deficits by 3, 3.5 and 4 points of GDP respectively. However, those countries are far from having the same track record: since the creation of the Eurozone in 1999, Italy has only had a primary deficit for five years (in 2009 and since the pandemic), while France has had primary surpluses - some of them modest! - for only five years.

New spending needs

Rebalancing the budgets is all the more necessary as new financing needs loom on the horizon. The war taking place on Europe's doorstep and, more generally, the growing geopolitical risks are prompting many governments to increase their defence spending. Demographic ageing also imposes a growing cost on our societies (health, retirement, etc.). Last but not least, the energy transition requires major investment efforts, part of which will have to be borne by the public sector. The European Commission estimates that meeting its targets (Fit for 55 in particular) will cost the European Union an additional 620 billion euros per year. If the public sector takes on 40% of the costs, public spending will be 1.5 GDP points higher over the decade!

What role for the central bank?

Against this backdrop, the end of the ECB's purchasing programs - and even the deflation of its balance sheet - complicates the fiscal equation a little further: while the central bank has absorbed a significant proportion of sovereign issuance in recent years, the private sector will now have to pick up the slack. It is therefore essential to prevent the kind of dynamics we saw in the early 2010s. In this respect, the central bank today seems better placed to prevent any doubts about a country's solvency leading to panic! Within the framework of its PEPP program[1], it can still, for the time being, as it did in the summer of 2022, reinvest in the securities of a country that is under undue market pressure. Lastly, provided that the country's public debt is deemed sustainable, the ECB can activate a final tool (Transmission Protection Instrument) and intervene on the secondary market.

"The Times They Are a-Changin’ "

Exceptional fiscal support measures, approved by the European Commission, have greatly mitigated the shock of Covid and the effects of the energy crisis. However, the fiscal margins of some eurozone countries have been significantly eroded. Admittedly, tighter supervision of the banking sector - and higher capital requirements in particular - reduces the risk of a vicious circle emerging in which concerns about the solvency of banks and governments feed on each other. Admittedly, the average cost of debt will remain moderate for some years to come, as governments generally took advantage of low interest rates before the pandemic to extend the maturity of their debt. The volume of sovereign debt to be absorbed by the private sector will nonetheless be high in 2024 (just over €1,200 billion in gross issuance). Against a backdrop of high interest rates, unfavourable growth potential and substantial investment needs, the fiscal credibility of national governments could be tested.

For those countries in the worst positions, committing to putting their budgets back on a sustainable trajectory must be a priority. But the rebalancing must be gradual: at a time when new fiscal rules are being discussed, it is important to remember the sovereign debt crisis of 2011...